This report is one section of State Actions to Build the Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum. See the full resource guide.

SAMHSA lays out the essential elements and best practices for a no-wrong-door integrated crisis system in its National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care: a regional crisis call center, crisis mobile team response, and crisis receiving and stabilization facilities. These components are described below, along with specific state examples of noteworthy strategies and actionable resources to inform state policymakers in navigating the complexities of crisis care reform.

Regional Crisis Call Centers

In July 2022, the nation transitioned to 988, a three-digit national suicide and crisis line designed to be easily remembered. Kaiser Family Foundation notes that since 988’s launch through May 2023, the crisis line handled nearly 5 million contacts, of which nearly 1 million are from the Veteran’s Crisis Line — a part of 988 — with the rest consisting of 2.6 million calls; more than 740,000 chats; and more than 600,000 texts. 988 operates through the existing National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. With the transition to 988, there is an opportunity to emphasize state-level processes for crisis call centers, particularly through a regional approach. A regional approach supports customized responses that direct callers to local resources, targets funds to high-need areas, and allows for collaboration among components of rural and under-resourced areas. While the national lifeline routes calls to providers nearest to callers, states aim to answer as many of their locally originated calls as possible. Challenges such as staffing and provider availability may sometimes make it impractical to handle all calls at the state level. In such cases, calls are redirected back to the national number for assistance.

SAMSHA’s 988 Partner Toolkit provides a host of resources on 988 rollout and communication strategies. Regional crisis call centers provide people in crisis with immediate access to a live person at any time. Regional, 24/7, clinically staffed call hub/crisis call centers provide telephonic crisis intervention services to all callers, meet National Suicide Prevention Lifeline operational guidelines regarding suicide risk assessment and engagement, and offer air traffic control quality coordination of crisis care in real-time. Increasingly, regional crisis call centers also provide text and chat options. These mental health, substance use, and suicide prevention lines must be able to take all calls, triage the calls to assess the additional needs, and coordinate connections to additional support based on the assessment of the team and the preferences of the caller.

Virginia invested $9.8 million in a regional crisis call center approach and established an Office of Crisis Supports and Services. The state’s National Suicide Prevention Lifeline providers answer crisis calls for the majority of the state. Crisis workers evaluate callers’ situations, help de-escalate the crisis when possible, and collaborate with local social service boards, private providers, and 911 centers to connect callers with appropriate services. This regionalized approach integrates public and private resources to support callers in receiving comprehensive care, regardless of where they live in the state. Each regional hub (state fiscal agent that subcontracts with the call centers) will have memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with service providers in their area. The MOUs allow private crisis providers to bill Medicaid or other insurance, or when available, receive payment from the regional hub if the provider serves an uninsured person.

The three-digit calling code for the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline launched in July 2022. States continue to address necessary components for implementation, such as funding, workgroups to drive 988 policy, and integrating 988 into existing crisis call systems. Explore state-enacted legislation to implement and fund 988 through the map.

Mobile Crisis Team Response

Mobile crisis teams provide services wherever the person in crisis is located. Community-based mobile crisis services use face-to-face professional and peer intervention. Community-based mobile crisis programs often use interdisciplinary teams that include both licensed and non-licensed crisis workers. In addition to providing more person-centered approaches, these teams support emergency department and justice system diversion. Emergency medical services (EMS) should be aware and partner as warranted.

Mobile Crisis Resources

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) establishes an enhanced 85 percent federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) opportunity for mobile mental health crisis team services in Medicaid.

States may need to review and revise Medicaid state plans or other authorities in order to take full advantage of the enhanced FMAP opportunity. For states that deliver these services through managed care, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance indicates that qualifying crisis services must also be included in plan contracts and the costs of those services integrated into corresponding capitation rates.

State Examples

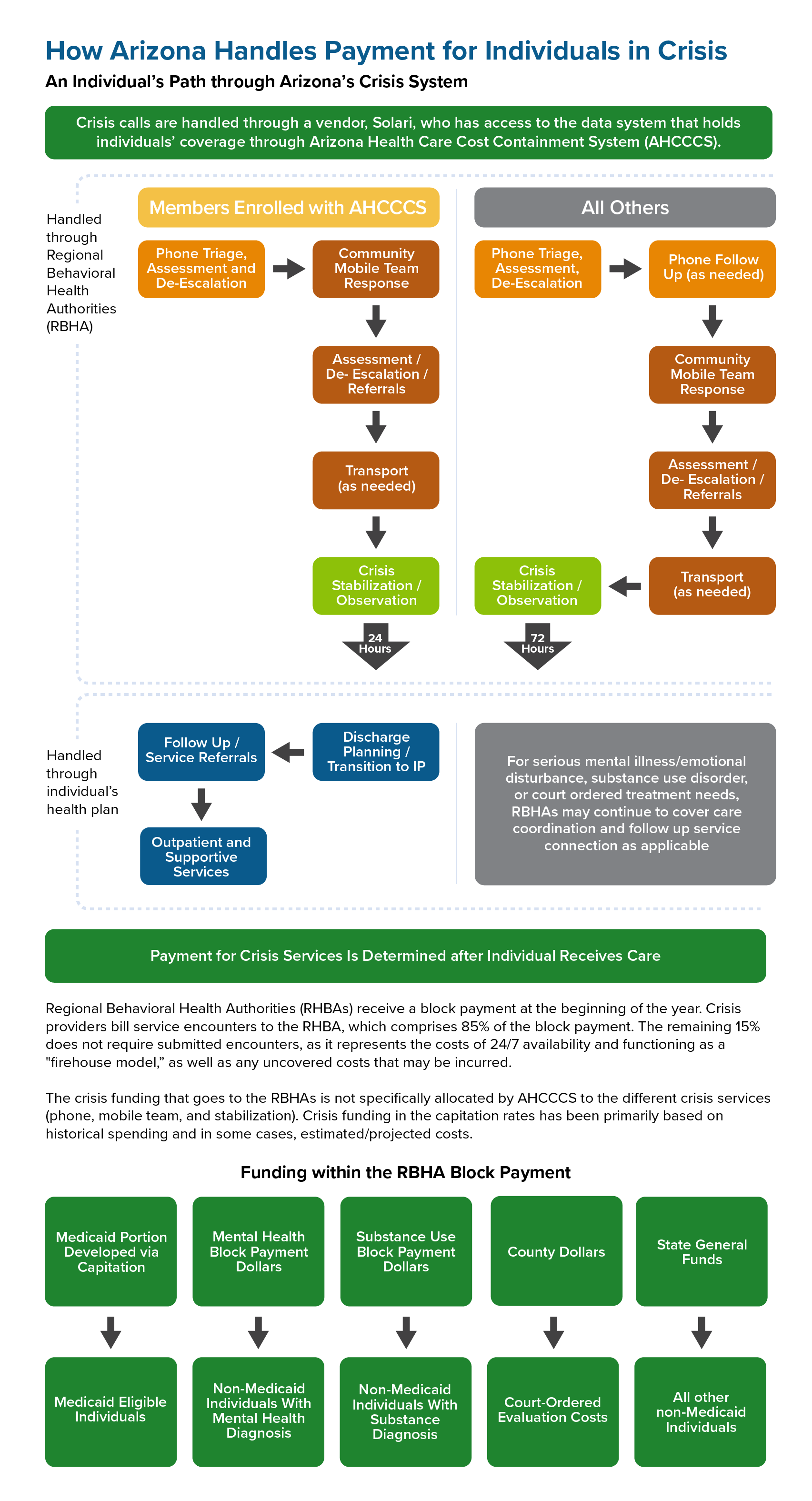

Washington and Arizona created regionally based systems to cover more territory in a timely manner and provide financial support to mobile crisis response in less densely populated areas. In both states, crisis response is available regardless of insurance status and can be administered through managed care.

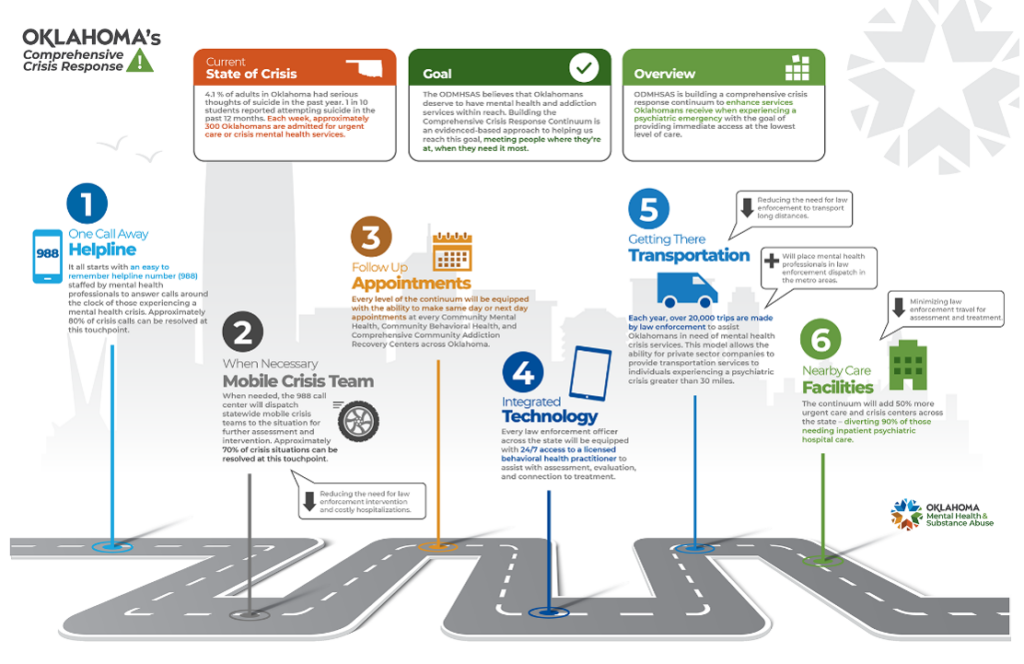

Many states, including South Carolina, South Dakota, and Oklahoma, have expanded behavioral health assessment capacity by supplying computer tablets to first responders, allowing them to connect directly with behavioral health clinicians. These efforts support rural communities in accessing behavioral health support and reduce unnecessary hospital transports for individuals who could be stabilized in the community.

Georgia implemented a decision tree to help call center staff triaging calls determine appropriate responders (e.g., whether law enforcement should be involved). Because Georgia has a statewide crisis number, the same process will support all callers.

Connecticut created a monthly learning collaborative for mobile crisis team providers to share best practices and support workforce collaboration. The example highlights different ways states are facilitating knowledge sharing and collaborative problem-solving to enhance the effectiveness of mobile crisis services.

Example of a State Vision for Crisis System

Oklahoma’s Comprehensive Crisis Approach in 2022 includes an array of services critical to establishing a comprehensive continuum of care.

Crisis Receiving and Stabilization Facilities

Crisis receiving and stabilization services provide no-wrong-door access to mental health and substance use care, operating much like a hospital emergency department that accepts all walk-ins, ambulance, fire, and police drop-offs. These facilities accept all mental health crisis referrals and are staffed to work with people of all ages and potential clinical conditions — regardless of acuity. These facilities make it possible for first responders or walk-in referrals to avoid emergency department visits and justice system involvement. If an individual’s condition requires medical attention in a hospital or referral to a dedicated withdrawal management program, the crisis receiving and stabilization facility makes those arrangements.

State Examples

Missouri implemented Behavioral Health Crisis Centers (BHCCs) regionally across the state. BHCCs provide law enforcement drop-off locations for individuals in a behavioral health crisis and are designed to divert people from jail, prison, and emergency departments. The BHCCs are strategically placed near Missouri state trooper offices to encourage a regional approach. Several of the BHCCs are open 24/7, and others operate on an “urgent care” model.

Arizona has piloted a “no-wrong-door” policy in crisis care, meaning that law enforcement officers are never turned away, eliminating the need for them to navigate a complicated system of hospitals, substance use providers, or clinics. The drop-off process is less than 10 minutes, which is considerably faster than what it would be at a jail or emergency department. Services include 24/7 walk-in urgent care and 23-hour observation. Law enforcement escorts many individuals directly from the field, with others arriving by mobile crisis teams, walk-in, or transfer from emergency rooms. Through rapid assessment, early intervention, proactive discharge planning, and close collaboration with community providers, the majority of patients are stabilized and connected to appropriate community-based care without the need for hospitalization.

It is worth noting that for those who need it, a 15-bed adult subacute unit provides three to five days of continued stabilization. Crisis triage and stabilization acts as a least restrictive alternative setting and offers a no-wrong-door approach to services. The stabilization facility has the ability to provide seclusion and restraint. Seclusion and restraint is a last-resort option, but it is a licensure requirement that allows the facility to take anyone who comes into their building, regardless of acuity.

Most states have no licensure that covers 23-hour crisis stabilization, which poses a payment puzzle for covering the costs. Most payment options favor crisis stabilization facility licensing as an outpatient facility, which does not allow for seclusion and restraint. Seclusion and restraint is a worst-case scenario, but many people with involuntary involvement in the mental health system may not be permitted admission into facilities without seclusion restraint protocols — this then leads to those individuals arriving at emergency departments for care. States modernizing the crisis continuum face complexities and gaps in payment and licensure frameworks for crisis stabilization facilities, necessitating comprehensive evaluation and potential policy reforms to ensure appropriate care and a responsive, inclusive system that meets diverse needs.

Important Additional Components to Crisis Continuum

The National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care emphasize the importance of having a comprehensive crisis system that includes essential elements such as providing individuals with someone to talk to, someone to respond, and somewhere to go. In addition to these core elements of a crisis system, other components such as short-term residential facilities and peer-run respite options help ensure individuals a path to recovery and support a full crisis continuum of care. This section highlights some examples of states taking steps to implement these elements of care.

Short-Term Residential Facilities

Small, home-like, short-term residential facilities can be seen as a strong step-down option to support individuals who do not require inpatient care after their crisis episode. To maximize their usefulness, short-term residential facilities can function as part of an integrated regional system of care. Access to these programs can also be facilitated through a regional call center hub to maximize system efficiency.

State Examples

Rhode Island’s Providence Center’s Crisis Stabilization Unit (CSU) provides short-term care for people amid acute behavioral health crises that might escalate to a level of acuity requiring hospitalization. As an alternative to hospitalization or as a step-down for a transition between levels of care, the CSU’s services focus on stabilizing clients and addresses their mental health and substance use needs.

Ohio has established home-like environments in psychiatric residential treatment facilities for its youth covered by Medicaid. These facilities focus on engagement strategies, linking individuals to community-based care, family friendly environments, minimizing trauma experiences, and reducing restraints. These environments include sensory rooms, weighted blankets and other sensory-sensitive tools, attention to the unique physical needs of youth, and soothing plans developed with each youth in services.

Peer-Operated Respite

Peer-operated crisis and respite programs offer people an alternative to more clinical settings. Staffed by people with lived experience in mental health and substance use issues, these programs focus on the wide array of supports that people can access and build to achieve recovery for themselves.

State Examples

New York partners with providers like People USA, a 100 percent peer-run organization, to support the expansion of innovative wraparound crisis services to individuals through a forensic mobile crisis team, crisis stabilization units, and Rose Houses, a voluntary short-term crisis respite that provides a home-like alternative to psychiatric units; all services are funded through braided funding that includes hospital and county funding. People USA reports that each Rose House saves the health care system on average over $6.57 million each year. While these services cannot be billed to Medicaid, New York and other states are exploring options for the development of crisis stabilization facilities using state general funds and Medicaid section 1115 demonstration waivers.

Massachusetts is home to the Kiva Centers, a peer-run and trauma-informed organization that offers training, technical assistance, and networking opportunities statewide as well as a peer-operated respite. Kiva Centers has a team of mobile peer respite advocates that offer support anywhere in Massachusetts up to four hours at a time on multiple days a week. In addition, the Kiva Centers include a six-bedroom house where 24/7 peer support assists visitors with navigating trauma and/or emotional distress. Massachusetts supports the peer respite model with a monthly payment rate.

In Georgia, residents can access Peer Support and Respite Centers that are peer-run rather than traditional mental health day programs and psychiatric hospitalization. Each of the five Peer Support and Respite Centers in the state has respite rooms available 24 hours a day year-round. The three or four respite rooms at each center are free of charge and can be occupied by anyone who thinks they would benefit from 24/7 peer support, for up to seven nights every 30 days. Georgia defines these services in its behavioral health provider manual.