State price-gouging laws (PGLs) seek to prohibit and authorize action against the practice of offering prescription drugs for sale at an unconscionable or excessive price. During the 2018-19 legislative session, at least 15 states considered price-gouging legislation specific to prescription drugs. As of March 10, 2020, NASHP was tracking pending legislation in four states.

When state PGLs have become law, they have encountered tough challenges in the courts, leading to high-profile adverse decisions about laws adopted by Washington, DC and Maryland. The US Supreme Court has not weighed in in these cases, and commentators question whether courts in other parts of the country would rule in the same way; however, these rulings may have a chilling effect on states. This brief addresses the question, given the legal obstacles encountered to date, how can the price-gouging model be successful at the state level going forward? It outlines the key legal challenges state PGLs may face and offers recommendations for surmounting them.

What do state prescription drug price-gouging laws (PGLs) do?

To combat excessive drug prices, PGLs may focus on a drug’s base price, the magnitude of price increases over a defined period of time, or both. Laws regulating price increases typically examine whether the change in a drug’s price exceeds a specified benchmark on an annual basis or cumulatively over several years. One approach is to adopt a law that applies all the time and caps price increases at the rate of inflation or a defined percentage increase. Another approach is to have the law apply only during a declared emergency and define the illegal increase in terms of whether a “gross disparity” exists between the price before and after the emergency declaration. Laws may provide that price-gouging penalties are automatically triggered or may provide that a presumption of price gouging is established if the benchmark is exceeded but allow the manufacturer to rebut it by showing its cost increase was justified. (For example, because a market disruption made it more costly to acquire ingredients). Penalties in PGLs may take a variety of forms, from a tax on the excess amount to traditional remedies for unfair business practices available under state consumer protection statutes.

Laws can also regulate a drug’s base price, i.e., the price it is today, or the price at which a new drug is launched. Such an approach would need to specify the unit to which the price applies — e.g., a month’s supply at the most commonly prescribed dose. A dollar cap could be specified or the law could peg the maximum price to some external reference, such as prices in other high-income countries (although the latter may involve heightened risk of a dormant or foreign Commerce Clause problem, as discussed below). Regulating both base price and price hikes makes price regulation harder to evade. Otherwise companies can skirt laws focused on price increases by launching new drugs at a high price and evade base-price regulation by launching low with a plan to raise prices significantly over time.

An important decision that state lawmakers must make for PGLs is which price to assess (Table 1). Although average sales price (ASP) is the best indicator of what purchasers in the United States are actually paying, because of data limitations, PGLs generally specify either the average manufacturer price (AMP) or wholesale acquisition cost (WAC). State drug price transparency laws generally use the WAC. The AMP more closely approximates actual prices than the WAC.

Table 1. Understanding Different Drug Prices1,

| What is it? | Advantages | Disadvantages | |||

| Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) | Offering (“list”) price set by the manufacturer for wholesalers and direct purchasers, before discounts and rebates |

|

|

||

| Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) | Average price actually paid by wholesalers for drugs distributed to the retail pharmacy class of trade, after prompt-pay discounts but before rebates |

|

|

||

| Average Sales Price (ASP) | Manufacturer’s unit sales of a drug to all US purchasers in a calendar quarter divided by the number of units sold, after all discounts and rebates (except Medicaid rebates). |

|

|

||

What legal challenges did PGLs in Maryland and Washington, DC face?

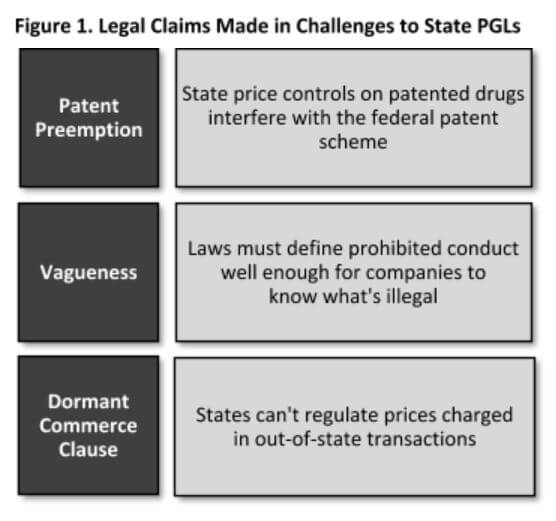

The biopharmaceutical industry has challenged PGLs laws on a number of grounds, but the most important are patent preemption, vagueness, and dormant Commerce Clause (Figure 1).1

Patent preemption claims allege that a state law impermissibly intrudes into a policy area that the Constitution reserves to the federal government: patent rights. For example, Washington, DC’s Prescription Drug Excessive Pricing Act of 2005 prohibited drug manufacturers or their licensees (except retailers) from selling patented prescription drugs in DC “for an excessive price.” “Excessive” was defined by reference to prices paid in other high-income nations. In a case known as BIO, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the DC District Court’s decision that this scheme interfered with patent rights by penalizing high prices, and therefore upset the balance established by Congress in the patent system between giving incentives for innovation and ensuring access to patented products.3 Mindful of the BIO decision, Maryland chose to limit its PGL, known as HB 631, to off-patent or generic drugs for which all federally granted market exclusivities had expired.

Patent preemption claims allege that a state law impermissibly intrudes into a policy area that the Constitution reserves to the federal government: patent rights. For example, Washington, DC’s Prescription Drug Excessive Pricing Act of 2005 prohibited drug manufacturers or their licensees (except retailers) from selling patented prescription drugs in DC “for an excessive price.” “Excessive” was defined by reference to prices paid in other high-income nations. In a case known as BIO, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed the DC District Court’s decision that this scheme interfered with patent rights by penalizing high prices, and therefore upset the balance established by Congress in the patent system between giving incentives for innovation and ensuring access to patented products.3 Mindful of the BIO decision, Maryland chose to limit its PGL, known as HB 631, to off-patent or generic drugs for which all federally granted market exclusivities had expired.

Vagueness challenges assert that a law’s definition of price gouging is so ambiguous that it fails basic requirements of constitutionally protected due process rights. Courts have interpreted the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment to require states to ensure that people have fair notice of what constitutes illegal conduct and that officials enforcing the law have standards to govern their decisions.

Vagueness arguments were deployed against Maryland’s HB 631, which barred manufacturers from engaging in “price gouging” for generic or off-patent drugs that were “essential” and made by 3 or fewer manufacturers. The law defined “price gouging” as “an unconscionable increase” in the price of a drug, which it in turn defined as an increase that is (1) “excessive and not justified” by the cost of making the drug or expanding access to it, and that (2) results in consumers “having no meaningful choice” but to buy the drug at that price the drug is important to their health and the market has insufficient competition. The legislature further signaled what might constitute excessive pricing by authorizing Maryland’s Medicaid program to notify the state attorney general if there was an increase of 50 percent or more in a drug’s WAC that hiked the drug’s cost to $80 for more for defined periods of time, doses, or courses of treatment. Once notified, the attorney general could seek an injunction, restoration of money acquired through illegal pricing, and civil penalties.

The biopharmaceutical organizations challenging HB 631 argued that these provisions did not give companies enough information to know what constituted an “unconscionable increase” or “excessive” price. The courts never ruled on their claim, except to deny Maryland’s request to dismiss it, because the case was decided on a different basis. Vagueness remains a viable avenue of challenge to state PGLs.

The dormant Commerce Clause is a judicial doctrine holding that states cannot regulate in ways that place undue burdens on interstate commerce. When a state PGL may be applied to business transactions that take place outside the state, it is potentially vulnerable to a particular kind of dormant Commerce Clause claim known as extraterritoriality. The extraterritoriality doctrine holds that “a state may not regulate commerce occurring wholly outside of its borders.”,

Such claims were brought in the Washington, DC case. The federal district court held that any application of the DC law to transactions outside the district’s borders would indeed violate the dormant Commerce Clause. (Washington, DC did not appeal that holding.)

A dormant Commerce Clause claim was also successful against Maryland’s HB 631; a divided, three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals 4th Circuit held that the law could not be applied to situations in which both parties to a transaction are located out of state.4 The statute covered drugs “made available for sale in [Maryland],” many of which originated in a transaction between an out-of-state manufacturer and an out-of-state distributor. The court found that its practical effect was to control price in such transactions, which violated extraterritoriality. The act, said the majority, “is not triggered by any conduct that takes place within Maryland,” “controls the prices of transactions that occur outside the state,” and, if enacted by other states, “would impose a significant burden on interstate commerce.”4 A lengthy dissenting opinion argued that the majority’s conclusion conflicted with the rulings of several other federal circuit courts, which have limited application of the extraterritoriality doctrine to price control or price affirmation statutes that pegged in-state prices to out-of-state prices and discriminated against out-of-state actors.

*A price affirmation statute requires a seller to attest that it will not sell to others at a price lower than it gave the state.

How can patent preemption problems be avoided?

The clear route for a state to completely avoid legal challenges based on patent preemption is to follow Maryland’s approach and limit its PGL to off-patent drugs and biological products. This would include generic drugs and biosimilars as well as branded products for which all patents and federal regulatory exclusivities have expired but for which no generic or biosimilar competitors have emerged. The language in HB 631 is suggested for states that wish to take this approach: “off-patent or generic drug” is defined as “any prescription drug … for which all exclusive marketing rights, if any, granted under the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, § 351 of the federal Public Health Service Act, and federal patent law have expired,” as well as “any drug-device combination product used for the delivery of a drug for which all exclusive marketing rights under [those laws] have expired.”

This approach limits the impact of the law on overall prescription drugs costs, since the most costly products are branded drugs and biological products that are within their period of market exclusivity. However, the end of market exclusivity does not always herald the beginning of a competitive market. Many generic drugs lack competitors and are surprisingly expensive, and price increases for some generics have been large in recent years, provoking significant public concern., Lack of competition is a particular problem for off-patent biological products. Therefore, PGLs may have salutary effects on costs even without including on-patent products.

An alternative approach would be to include on-patent as well as off-patent drugs and biologics and hope that the BIO decision will not govern the disposition of the litigation that will likely follow. BIO has not often been applied by other courts to resolve questions about patent preemption, and legal scholars have argued that it misapprehends the nature of the patent right. Further, the court in BIO emphasized the fact that Washington, DC’s statute applied only to patented drugs. State PGLs that cover all products, whether on- or off-patent, might be distinguishable on the basis that they less clearly signal a state’s intent to disrupt the patent scheme.13, Yet it is important to recognize that the BIO court’s reasoning — that “penalizing high prices” serves to “rebalance the statutory framework of risks and rewards” in the patent system — applies to at least some extent whenever a state law includes patented products. There would be some risk of a successful patent preemption challenge to a PGL that included patented products.

To minimize this risk, states could include all products in the PGL but structure the law as a tax on excess earnings rather than an outright prohibition on charging an unconscionable price. This would further distance the PGL from the Washington, DC statute, which made price gouging unlawful and provided a public and private right of action to seek fines and damages. Because states are permitted to impose sales taxes on patented goods, courts could choose to view this type of PGL as distinguishable from laws that impose direct price controls.14 Their willingness to do so would likely depend on the magnitude of the tax: the higher the tax, the more it looks a penalty imposed to disrupt patentholders’ rights — as the Federal Circuit characterized Washington, DC’s law in BIO. A drawback to structuring the law as a tax is that consumers and health plans are not assured of lower prices at the point of sale. The prospect of paying the tax may act as a deterrent for excessive pricing, but if the tax is substantially less than 100 percent, it would be economically rational for sellers to maintain the high price and pay the tax. If price reductions did not occur, states could find ways to pass along the tax revenue they instead collected to consumers who have paid high prices — i.e., through tax credits or rebates — though this would involve both delay and administrative costs.

How can vagueness problems be avoided?

Several lessons can be learned from looking at vagueness challenges in other contexts relating to price regulation, including price-gouging laws that apply during times of emergency, state consumer lending laws, and how courts resolve contract disputes involving allegedly unconscionable price terms.1

First, among the potential approaches that PGLs could take to defining an excessive price, borrowing the “gross disparity” standard from other emergency price-gouging laws is not recommended. Even if agreement could be reached that it is reasonable to declare high drug prices to be an “emergency” as of some date, asking whether prices during emergencies are grossly higher than pre-emergency prices isn’t very helpful because drug prices arguably were already inflated in the pre-emergency period.

Second, PGLs that prohibit “unconscionable” prices will be interpreted by courts according to standard principles of contract law unless they specify a definition of that term. Falling back on the common law of contracts isn’t optimal because courts typically require a showing that the price is not only substantively unconscionable, but also procedurally unfair. That procedural standard is hard to apply to medicines at the population level. In contract disputes, courts typically look at whether the buyer was subject to coercion or surprise. States can argue that patients’ medical need for prescription drugs, especially when combined with a lack of alternative therapies in the market, creates a coercive situation. But there is adverse precedent from cases involving hospital bills holding that a person’s dire need for medical treatment isn’t enough to conclude that a medical bill is unconscionable from a procedural standpoint. Another problem is that in contract disputes, courts have assessed procedural unconscionability by looking at the characteristics of the particular buyer or class of buyers—whether, for example, the buyer(s) lacked education or sophistication. For prescription drugs, the buyer that transacts with manufacturers isn’t the patient, it’s a large purchasing organization, so it is hard to argue they are vulnerable to being taken advantage of.

States can avoid these pitfalls by putting a definition of “unconscionable” or “excessive” in the statute that says a showing of procedural unconscionability is not required. (For policy reasons, they may still wish to limit PGLs to drugs for which there aren’t many alternatives on the market, but it is better not to embed that choice in the definition of unconscionable price.)

Third, state consumer lending laws are an attractive model for defining unfair pricing practices for medicines.1 To address unfair lending practices, such as excessive interest rates, many states have taken a two-pronged approach. The have adopted (1) a usury statute that sets a maximum interest rate for consumer loans and (2) a general consumer protection act (sometimes called an Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices, or UDAP, statute) that prohibits a more general class of unconscionable business practices. For prescription drug prices, states could adopt both a maximum percentage cap on price increases in transactions covered by the statute and a more general statutory prohibition on selling drugs at an excessive price (Figure 2). The price increase law would address many of the pricing problems of greatest current concern and, because of its clear quantitative definition of what is excessive, would be straightforward to administer and enforce. The more general statute would serve as a backstop — a means of addressing high base prices that are not primarily due to recent, large price hikes. State attorneys general and/or individual consumers could bring actions under the general statute when they encounter an unconscionable price, just as they do for other unfair business practices under UDAP statutes.

This approach is attractive because it prevents gaming by companies (e.g., avoiding price hike regulation by setting launch prices higher). Additionally, states can write a definition of “unconscionable” or “excessive” base price into the statute that avoids tangles over procedural unconscionability. Finally, courts have repeatedly upheld consumer lending laws prohibiting unconscionable business practices against vagueness challenges. Case law concerning usury laws suggests that a maximum percentage increase for price hikes, too, would be highly defensible against vagueness claims.

Some guidance would, of course, need to be given as to what constitutes an excessive price. A variety of approaches could be taken — from establishing a dollar limit that the state considers unaffordable to its residents, given household income and living expenses in the state, to establishing criteria for evaluating price based on the clinical value of the drug.1 For reasons discussed below, establishing an unconscionable price by reference to what is charged in other countries or other states may involve some legal risk.

How can dormant Commerce Clause problems be avoided?

States could follow two pathways in addressing potential dormant Commerce Clause challenges: one with relatively high legal risk but higher potential reward, and another with lower risk but lesser reward. The core tradeoff to be considered is that confining a statute’s reach to transactions within the state avoids dormant Commerce Clause problems, but because for most states the transactions between drug manufacturers and wholesalers occur out of state, doing so may substantially limit the law’s impact.

Option 1 is to forge ahead with statutes that reach out-of-state transactions notwithstanding the 4th Circuit’s decision in Frosh. The language used in HB 631, drugs “made available for sale in” the state, could be used.

A variant of this strategy would be to tighten up the wording of HB 631 that the 4th Circuit panel found unsatisfactory, and might pass muster with other courts. The following language strengthens the connection to in-state transactions and borrows from state cigarette escrow statutes, which courts have upheld notwithstanding the fact that in some states the supply chain of manufacturers and distributors is wholly out of state: “It is a violation of this subtitle to impose an Unconscionable Price Increase, whether directly or through a wholesale distributor, pharmacy or similar intermediary or intermediaries, on the sale of a Covered Product to any consumer in the State.”*

The Frosh decision is sufficiently at odds with past precedents on the extraterritoriality doctrine** that courts in other jurisdictions may well decline to follow it, making Option 1 a reasonable choice for states outside the 4th Circuit.*** The potential payoff associated with Option 1 is considerable: price gouging laws would apply to transactions between manufacturers and wholesalers, which is where the action is in terms of establishing a drug’s price. Another advantage is that WAC can be used as a benchmark for assessing violations of the statute, because the transactions covered by the statute include wholesaler purchases. Information about WAC is easier to find than alternatives such as the AMP or ASP. The main drawback to Option 1 is that legal challenges are likely to be brought, citing Frosh, which could be expensive even if ultimately resolved in states’ favor. But because the Frosh decision “calls into question the constitutionality of numerous state antitrust and consumer protection statutes,”4 this may be a fight well worth fighting.

Option 2 is to try to stay within the 4th Circuit’s decision and tailor the statute more narrowly to in-state transactions. For example, the statute could specify that “It is a violation of this Act to sell a Covered Product in the State of X at a price that represents an Unconscionable Price Increase.” This language would encompass (1) transactions between in-state pharmacies and consumers and (2) transactions between in-state distributors and in-state pharmacies or consumers. It would not directly apply to transactions between manufacturers and wholesalers that take place out of state.

The expected effect of restricting the ultimate price of a drug is to influence bargains made upstream in the distribution system. For example, if a pharmacy is only permitted to sell a drug for $100, it will refuse to pay a distributor more than $100, and the distributor will in turn refuse to pay the manufacturer more than $100. However, nothing in the statute would ensure that effect. Two possible adverse outcomes are that (1) wholesalers or manufacturers would refuse to sell the product altogether in the state if they could not maintain a certain profit margin, or (2) in-state pharmacies and in-state distributors would suffer an economic squeeze if they could not obtain the price concessions they sought from out-of-state manufacturers or distributors.

Option 2 is thus on surer footing in terms of dormant Commerce Clause claims but potentially less effective in achieving its objective. An additional drawback is that because Option 2 focuses on pharmacy transactions, pegging prices to the WAC or AMP—which is not what pharmacies pay—might be hard to justify.

The legal defensibility of both Option 1 and Option 2 may be enhanced by (1) requiring that manufacturers and distributors who wish to sell in the state must route those products through a state-licensed distributor located in state and (2) explicitly applying the PGL to transactions involving such distributors. Many states already have a licensure requirement for entities that operate as drug wholesalers within their borders, although drug manufacturers aren’t required to use an in-state distributor. Although it would be a significant expansion of current requirements for licensure, a state could condition license renewal on compliance with the state’s PGL.

Such a licensure requirement would not only improve incentives for compliance, but provide a stronger nexus between the PGL and in-state transactions. A drawback of this approach is that requiring in-state distributors might itself provoke dormant Commerce Clause challenges. However, the Supreme Court has made clear that state regulation does not violate the dormant Commerce Clause merely because it forces changes in “the particular structure or methods of operation in a retail market.”

Finally, because of the clear precedent that price affirmation statutes violate the extraterritoriality principle, state PGLs should not define excessive price solely according to whether the price for in-state buyers is higher than the price for out-of-state buyers, including buyers in foreign countries. Although courts have not spoken clearly about whether using prices in other high-income countries as a price benchmark violates the dormant or foreign Commerce Clause, the trial court in BIO hinted that it could, if applied as “a formulaic approach” or exclusive means of determining whether a price is excessive.9

Summary: Recommendations for State Lawmakers

Summarizing the foregoing, we offer the following suggestions for state PGLs (Table 2).

Table 2. Recommended Design Choices for State Price-Gouging Laws

| Which products should be covered? |

|

| Which transactions should be covered? |

|

| Which price should be assessed? |

|

| How should the maximum allowable price increase be specified? |

|

| How should an excessive base price for a drug be defined? |

|

| When enforcing the law, which products should state agencies target? |

|

| Other |

|

* Indicates an option with somewhat elevated risk of legal challenge, but considerably greater potential payoff in terms of improving access to affordable medicines.

Notes and Acknowledgements

*Michelle Mello, PhD, JD, is a professor of Law, at the Stanford Law School and a professor of Medicine at the Stanford School of Medicine.

Acknowledgements: The National Academy for State Healthy Policy’s Center for State Rx Drug Pricing, with support from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, commissioned this analysis. This brief is adapted in part from Michelle M. Mello and Rebecca E. Wolitz’s article, Legal Strategies for Reining in “Unconscionable” Prices for Prescription Drugs, 114 Northwestern L. Rev. 859 (2020). The full article can be downloaded at https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/nulr/vol114/iss4/1/. Michelle Mello’s contribution to this brief was as a paid consultant, and was not part of her Stanford University duties or responsibilities.