Contact tracing, a strategy long-used to contain the spread of infectious diseases by identifying and isolating people exposed to an infection, has become a crucial state tool to curb COVID-19. But the pandemic requires significant ramping up of contact tracing capacity and funding. Experts estimate 30 contact tracers are needed for every 100,000 Americans — a total of 98,460 workers nationwide — far short of states’ current tracer workforces.

Confronted with looming budget shortfalls and unknown future federal relief funding, state health departments are taking a variety of approaches to scale up contact tracing. Some are working in-house to increase their state and local workforces, others are partnering with other organizations to secure staffing, training, and recruitment assistance, and others are contracting with a third party.

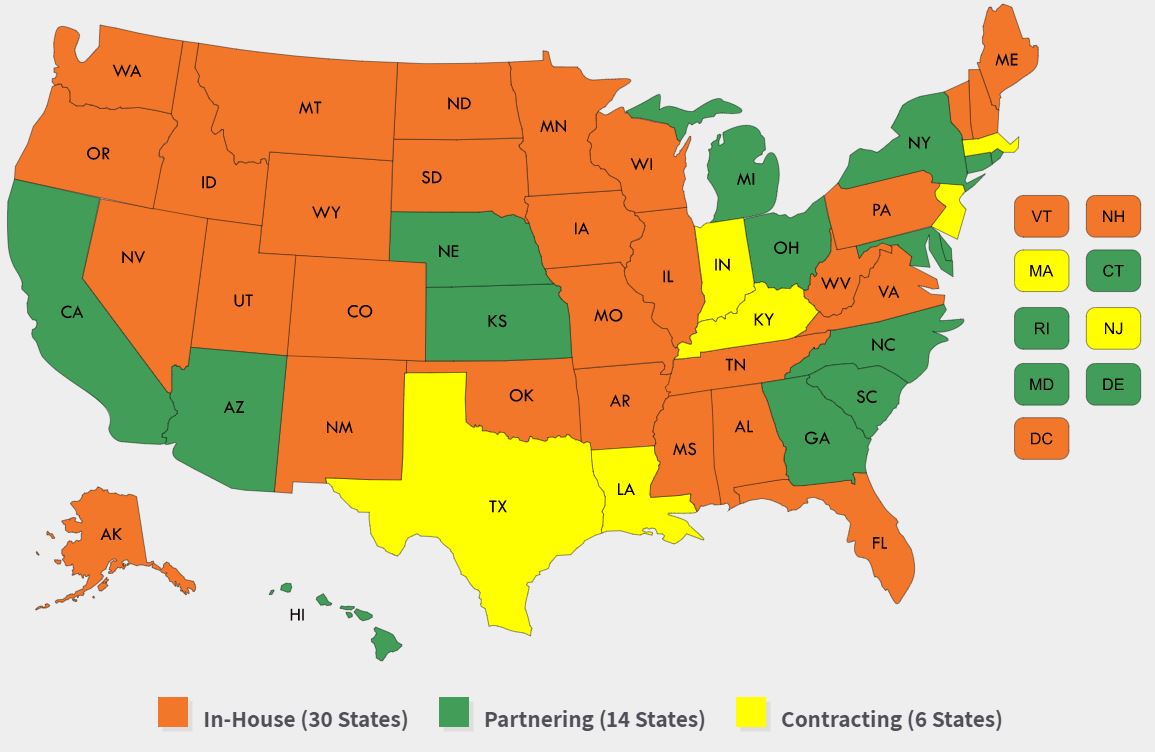

The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) created an interactive map highlighting how every state and Washington, DC, is innovating and expanding its contact tracing capacity to contain the infection and reopen its economy. Several examples of each model type are described below.

This interactive map highlights each state’s contact tracing program model, workforce, lead agencies, funding, and technology.

In-house: As of late May 2020, more than half of the states are managing contact tracing in-house by increasing their workforces. Many are reassigning internal health department staff along with county and state employees to contact tracing roles, including swimming pool and restaurant inspectors in Nevada and police in Colorado. Washington, DC and several states are hiring contact tracers. DC will use $2.3 million from the city’s contingency ccash reserve fund for its initial hires. Many states are increasing their workforce by seeking volunteers, including Wisconsin, which created a State Emergency Operations Center to organize and train contact tracers and coordinate volunteers from its Emergency Assistance Volunteer Registry. States are also engaging students and partnering with universities, including North Dakota, whose public health graduate students are receiving course credit for their contact tracing work. Several other states, including Delaware, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Washington State, and West Virginia have brought in the National Guard for contact tracing assistance.

- Partnering: Several states have formal partnerships or contracts in place to support their contact tracing efforts. Many states are pursuing this option to train contact tracers. In California, where the state and local health agencies are managing a paid and volunteer workforce, the state awarded an $8.7 million contract to the University of California, San Francisco, to provide training and technical assistance to local health departments. The University of Hawaii Community Colleges are providing training and adding capacity in their community health worker programs so that community health worker graduates will be prepared to support COVID-19 contact tracing in Hawaii. Other states are partnering with third parties to supplement staffing or facilitate recruitment and hiring efforts. In Michigan, the private company Rock Connections will manage volunteers, and Deloitte will manage technology for the state’s tracing program. In North Carolina, the state health department launched the Carolina Community Tracing Collaborative, partnering with two local health care delivery and education organizations, along with Partners in Health, to coordinate with and build on existing contact tracers in local health departments.

- Contracting: Six states have announced plans to contract a large portion of their contact tracing work out to a third party. These states are contracting with private companies or nonprofit organizations, some with call-center settings, to take over or augment a state’s contact tracing workforce. In Indiana, the state awarded a $43 million contract to a private health and human services company, Maximus, to hire about 500 people to staff a call center and manage the state’s ongoing contact tracing effort. State health department officials say this will preserve capacity for state and local health officials to intervene in settings that are at higher risk for outbreaks. Similarly, Texas is contracting with the private technology company, MTX Group, at a cost of nearly $300 million for a 27-month contract to build and manage a group of contact tracers, with a goal of building a workforce of 4,000 tracers. New Jersey announced its Community Contact Tracing Corps will centralize its effort and will be staffed with partnerships with colleges and universities as well as a contract with a vendor. NASHP recently detailed Massachusetts’ Contact Tracing Collaborative, a unique model with the nonprofit Partners in Health, which is managing a virtual support center of up to 1,000 people when fully staffed.

States also vary in their approaches to contact tracing, with some creating a centralized effort led by the state health department and others using an approach led primarily by local health agencies with state support and coordination. In Montana, the state is supporting local efforts through the creation of a grant program using $5 million in federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding, in part, for local health departments, tribal public health, and urban Indian clinics to enhance their COVID-19 contact tracing efforts. New Jersey is shifting to centralize its efforts by building a contact tracing corps that will supplement work that has primarily been led at the local level to date.

In addition to creating a robust contact tracing workforce, states are pursuing a variety of technologic solutions to supplement or facilitate this work. Several states are using automated symptom monitoring systems that allow those who have been in contact with someone with COVID-19 to report symptoms daily. Arizona’s secure, automatic 14-day symptom monitoring and reporting system allows contacts to report symptoms to public health daily by phone, text, or online. Other technological strategies range from statewide platforms that allow the state health department to share data with contact tracers to apps that use Bluetooth location technology to notify users when they have been near someone with COVID-19. The utility of these novel apps remains uncertain due to technical difficulties, public distrust, and potential privacy concerns.

How States Are Funding Contact Tracing

Contact tracing is a costly endeavor, with states reporting spending millions to staff up and create infrastructures either internally or through third parties. The National Association of City and County Health Officials, and other public health associations, have called on the federal government to provide $7.6 billion in emergency supplemental funding to public health agencies to assemble this nationwide team.

In Ohio, the state Controlling Board approved use of federal COVID-19-related funding, including $12.4 million for local health departments for contact tracing in May and June. Virginia committed $58 million in federal emergency aid to expand contact tracing and a pending state bill in Minnesota would direct up to $300 million for contact tracing-related costs, including staffing, a public service campaign, and technology.

While many states report using CARES Act funds (or other federal funds) for their contact tracing efforts, some will also use funds from private donors. Kaiser Permanente Colorado contributed $1 million for suppression of COVID-19 among homeless individuals in Denver and Bloomberg Philanthropies is investing $10.5 million and partnering with Johns Hopkins University for recruitment, training, and deployment of 3,500 contact tracers for New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Other private businesses are donating staffing resources – in Massachusetts, Blue Cross Blue Shield provided staff for the state’s contact tracing initiative.

Contact tracing for COVID-19 presents states with an unprecedented challenge that they are meeting by employing unique and creative strategies. With public health funding falling as a proportion of health spending since the early 2000s, chronic under-funding of state and local health agencies has limited states’ ability to quickly scale up to address emergencies. Federal support, collaborative and contractual relationships, and technology solutions are enabling states to take on this evolving need. NASHP will continue to track this dynamic issue and update its State Approaches to Contact Tracing during the COVID-19 Pandemic interactive map over time.